ASKE-E Month 9 Milestone Report¶

Integrating the COVID-19 Disease Map community model¶

One of our goals in this project is to demonstrate the capability to take an existing model constructed by others in the community and instantiate it as an EMMAA model. One approach for doing this is to take the model in its original form and extend it with some meta-data to allow running it for the purposes of validation and analysis within EMMAA. Another approach is to process the original model into knowledge-level assertions - in our case INDRA Statements - and instantiate this set of statements as an EMMAA model. As the first proof of principle, we decided to take the latter approach since it results in a more transparent model with all necessary annotations available to display model statistics, testing and query results on the EMMAA dashboard. Due to its direct relevance to our applications and its interesting connection with our existing automatically assembled COVID-19 EMMAA model, we decided to work with the COVID-19 Disease Map model.

The COVID-19 Disease Map (C19DM) is a large model of molecular mechanisms related to SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 curated collaboratively by a consortium of experts. It models all known SARS-CoV-2 protein interactions with human host proteins, and multiple pathways that are triggered by these interactions. It also models phenotypic outcomes associated with COVID-19, for instance, cytokine storm, thrombosis, vascular inflammation, ARDS, etc.

The C19DM is being built using CellDesigner and can be explored or programmatically obtained through the MINERVA platform. Using the CASQ tool, the model has also been transformed into a Simple Interaction Format (SIF) that can be used as the basis for causal analysis or Boolean/logical modeling.

We implemented a new client and processor in INDRA to process the C19DM SIF files in conjunction with metadata (entity grounding, literature references, etc.) from MINERVA into INDRA Statements. We then initialized an EMMAA model with these statements (see model card below).

The next step was to set up the model for automated analysis against a set of relevant empirical observations. We chose three sets of observations to analyze the model against: (1) a set of in-vitro drug screening experiments, (2) a set of empirical assertions on drugs inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection or adverse outcomes associated with COVID-19 (aka the MITRE test corpus), and (3) text mining statements automatically collected by the existing EMMAA COVID-19 model. We used both signed graph and unsigned graph instantiations of the C19DM EMMAA model for analysis.

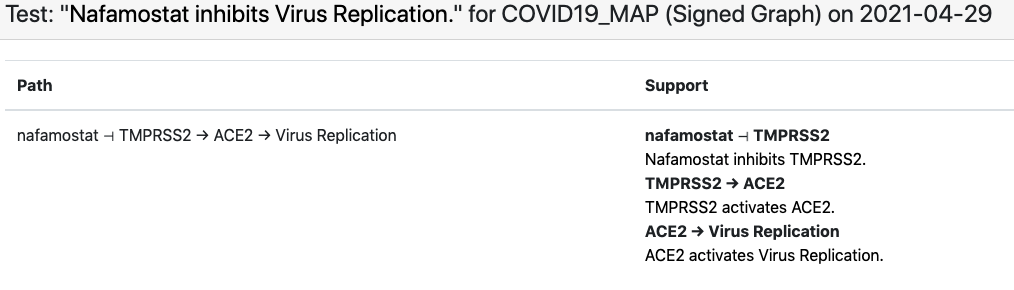

In case of the in-vitro drug screening data, each data point can be interpreted as “Drug X inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication”. Viral replication appears as a concept in the C19DM model and can be used as a readout in this case. However, most drugs that appear in the screening data aren’t modeled in the C19DM. We therefore extended the EMMAA C19DM model with these drugs and their known targets within the C19DM using statements independently assembled by INDRA from multiple sources. The in-vitro drug screening corpus is relatively small and the EMMAA C19DM model (instantiated as a signed graph model) could explain 10 such observations, including how “nafamostat inhibits viral replication”. The explanation in this case involved nafamostat inhibiting TMPRSS2’s activation of ACE2 which enables viral replication:

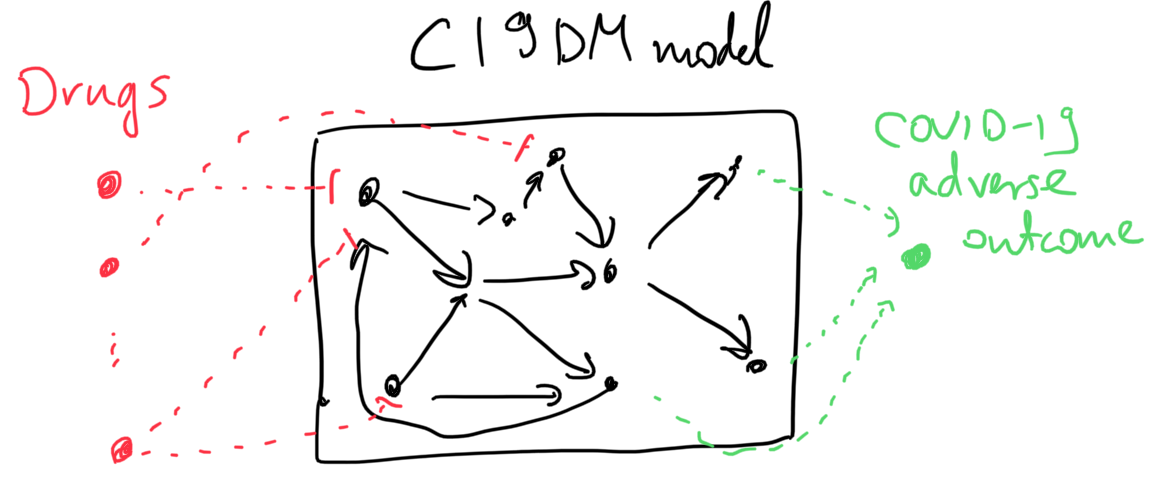

As for the second corpus, these empirical assertions aren’t necessarily associated with SARS-CoV-2 replication per se, rather, they imply that a given drug is beneficial in inhibiting some COVID-19-associated adverse outcome. While there are several phenotypic nodes that could be considered readouts for this purpose in the C19DM (e.g., thrombosis, cytokine storm, ARDS, etc.), we don’t want to assert up front which one of these a given drug affects. Therefore, we added a new readout concept to the model called “COVID-19 adverse outcome” and added positive regulation relations between each specific adverse outcome concept and this new one. Similar to the case of in-vitro drug screening as described above, we also added external drug-target statements relevant for this corpus.

The sketch below illustrates the two types of model extensions done to make the model applicable to these analysis tasks.

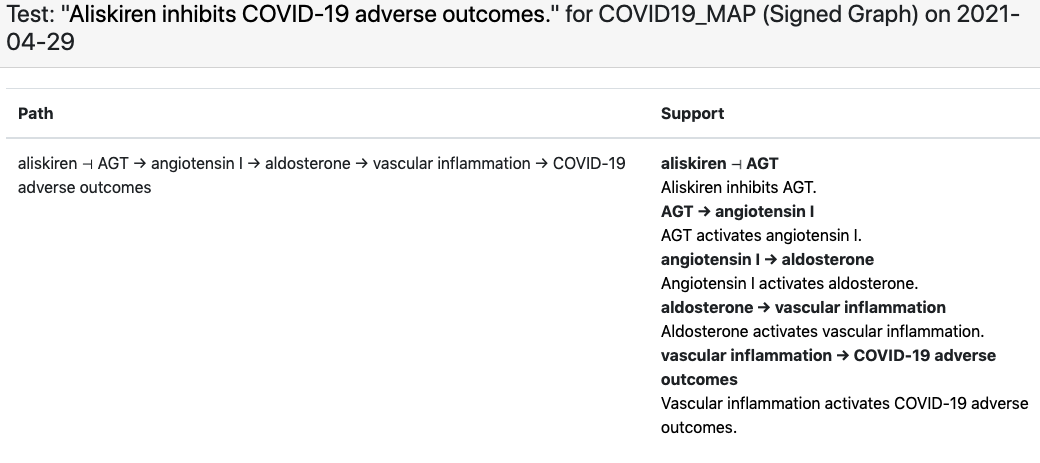

For this corpus the C19DM EMMAA model, instantiated as a signed graph was able to explain 463 test statements. It is particularly interesting to observe which specific phenotypic outcome the explanation involves as a “COVID-19 adverse outcome”. For example, for the observation that “aliskiren inhibits COVID-19 adverse outcomes”, EMMAA finds an explanation in the C19DM in which aliskiren inhibits angiotensin which - through some intermediaries - leads to reduced vascular inflammation, one of the adverse outcomes associated with COVID-19:

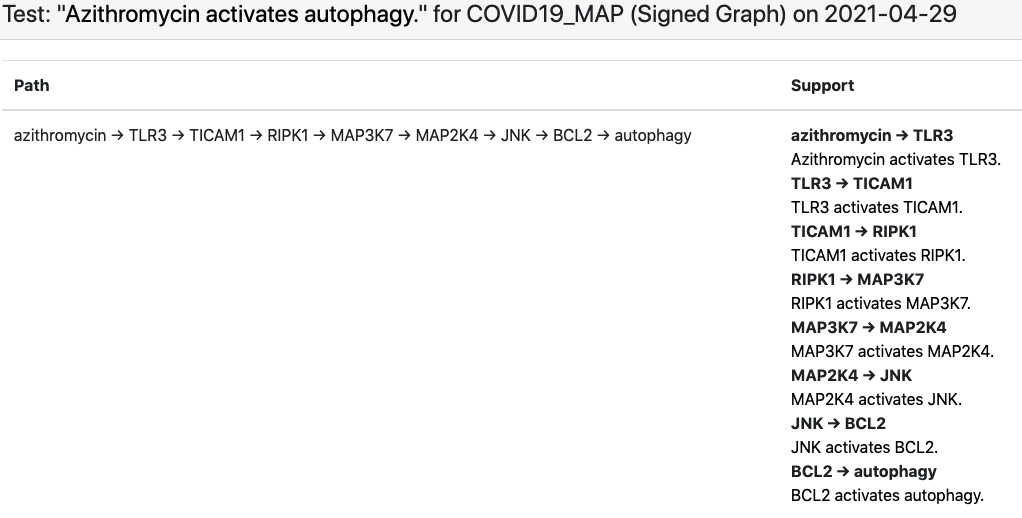

Finally, we set up the existing EMMAA COVID-19 model (which aggregates knowledge about COVID-19 largely via text mining the existing and emerging literature) as a set of assertions to be explained by the C19DM. Conceptually this is an interesting analysis task since the EMMAA COVID-19 model contains many assertions about indirect effects (e.g., “azythromycin activates autophagy”, see below) that were reported in the literature but not necessarily explained mechanistically, while the C19DM is a detailed, mechanistic and high-precision (in that it is human curated rather than automatically assembled) model that is likely to contain mechanistic paths that can serve as interesting explanations. As an example, below is the explanation constructed for the “azythromycin activates autophagy” example.

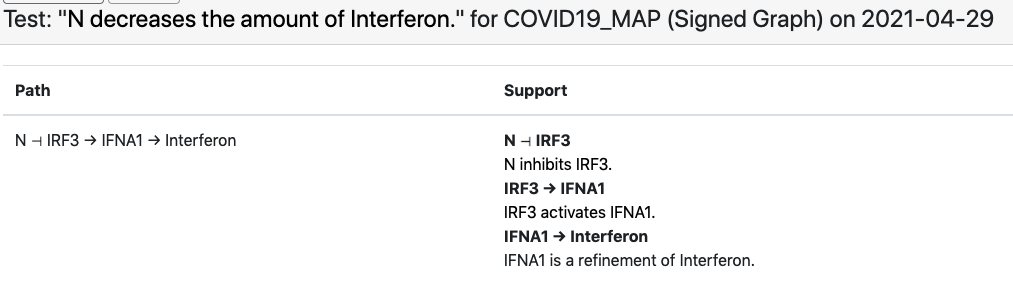

Another example involves the observation that “viral N protein downregulates interferon” which the EMMAA C19DM model explains through the SARS-CoV-2 N protein’s inhibition of human IRF3.

Going forward, we will work on instantiating the C19DM as a simulatable Boolean network within EMMAA and will also work towards importing other existing models into EMMAA for automated analysis.

Notifications about general model updates¶

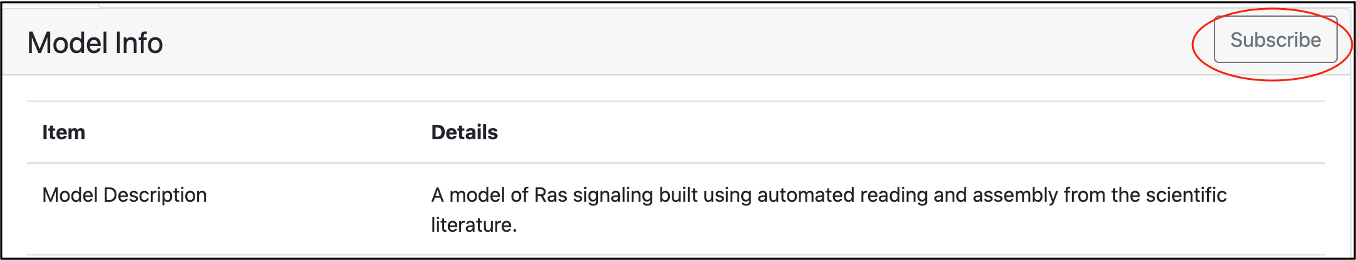

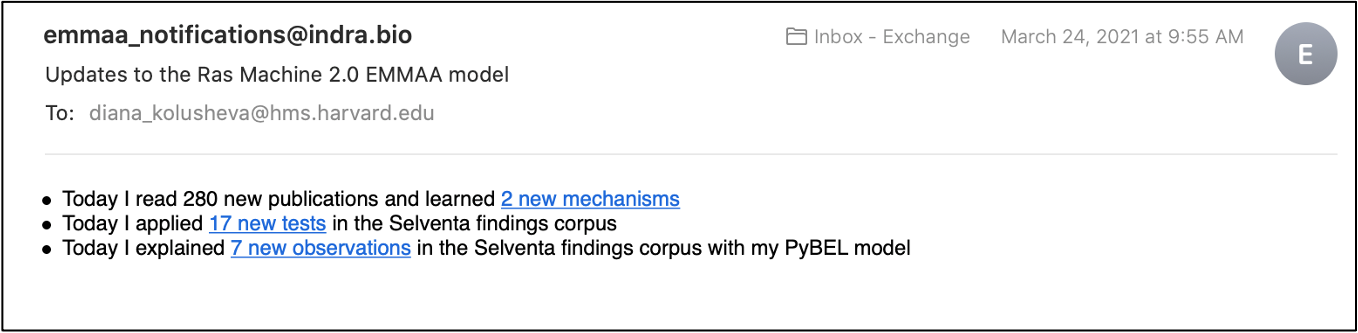

One of the key concepts of EMMAA is “push science” - notifying users of new discoveries relevant to their research. Previously reported developments in this direction included subscribing to query results and tweeting about new findings. We recently made a new step towards this goal and added a feature allowing users to subscribe to a model of their interest.

To subscribe to model notifications, a user needs to click the “Subscribe” button on the model dashboard. The models are updated and tested daily and every time there are any new findings, a subscribed user will receive an email with updates. New findings can include new mechanisms added to the model from the literature, new tests applied to a model, or new explanations found for the tested observations.

We refactored our code base to separate all code related to notifications (tweets and emails about model updates and emails about new query results) into a subscription.notifications submodule. This allows sharing and reusing relevant parts of code.

Figures and tables from xDD as non-textual evidence for model statements¶

We previously reported on displaying figures and tables from a given paper through the integration with the xDD platform developed by UW. That approach supports an exploration of different mechanisms described in the context of a single paper by viewing both their text description and visual representation.

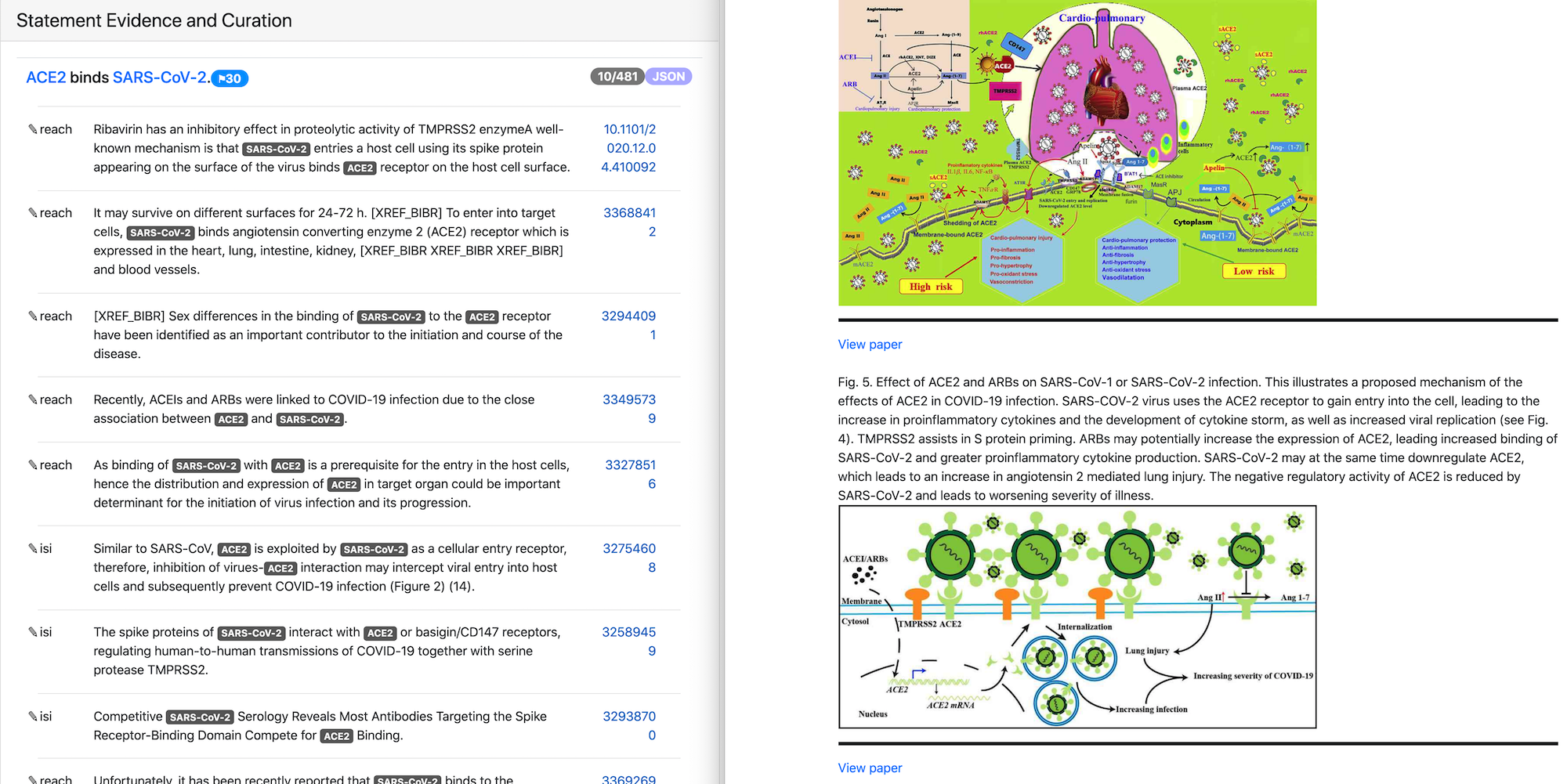

In this reporting period we added support for displaying figures and tables relevant for a given mechanism rather than for a particular paper. To enable this we used xDD entity based search mode that allows searching for objects associated with one or more entities across their knowledge base. For our use case we are searching for figures and tables where both statement subject and object are involved. As a result, we can display both textual and non-textual evidence for a given statement coming from different papers.

In the image above the text evidence and figures for the statement “ACE2 binds SARS-CoV-2” are shown. Both text and figures are from different papers and have links to the original publications.

Integration with the Uncharted UI¶

We continued working on the integration of EMMAA with the Uncharted UI and made progress on several fronts. Model exploration in the UI is divided into two parts, a large-scale network overview, and a more focused drill-down view.

For the network overview, our concept was to use the INDRA ontology - which is assembled from third-party ontologies in a standardized form - to hierarchically organize nodes in the network (each node represents a biological entity or concept) into clusters. This visualization is most effective and clear if the hierarchical structure of the ontology is fully defined, i.e., every entity is organized into an appropriate cluster, and the hierarchy is organized into an appropriate number of levels. Motivated by this, we spent considerable effort on improving the INDRA ontology’s inherent structure, as well as creating a custom export script which makes further changes to the ontology graph specifically to improve the visual layout in the UI.

We also added multiple new features to the EMMAA REST API to support UI integration. For example, we added an endpoint to load all curations for a given model, categorizing curated statement into correct, incorrect and partial labels. Another important feature is providing general information about entities in each model, including a description, and links to outside resources describing the entity. To this end, we implemented a new service called Biolookup (which will be separately deployed) that provides such information for terms across a large number of ontologies in a standardized form. We then added an endpoint in the EMMAA REST API which uses Biolookup to get general entity information and can also add model-specific entity information to the response.

Our teams have also been involved in many ongoing discussions. These included deciding on use cases, visual styles, and all aspects of the interpretation of EMMAA models in order to present them to users in an appropriate way.

Semantic separation of model sources for analysis and reporting¶

When creating a model of a specific disease or pathway, it often makes sense to add a set of “external” statements to the model to make it applicable to a specific data set. A typical example is adding a set of drug-target statements or a set of phenotypic “readout” statements to a model to connect it to a data set of drug-phenotype effects. These external statements should ideally not appear in model statistics. For example, for the COVID-19 Disease Map model, we marked all drug-target and penotype-readout statements as external since these were not part of the original model.

Another categorization of statements in models is “curated” vs “text mined”. For instance, the COVID-19 model combines statements mined from the literature with statements coming from curated sources such as CTD or DrugBank. Given that we use the COVID-19 Disease Map Model to automatically explain observations that appear in the COVID-19 Model, it makes sense to restrict these explanations to statements that aren’t “curated”.

To achieve this, we extended the EmmaaStatement representation to contain metadata on each statement that then allows the statements to be triaged during statistics generation and model analysis.

Assembling and analyzing dynamical models¶

During this period, we aimed to strengthen EMMAA’s capability to execute and analyze dynamical models. Previously, EMMAA’s dynamical queries supported checking “unconditional” properties, for instance, whether in a model “phosphorylated BRAF is ever high”. This captures a model’s baseline dynamical behavior without any specific perturbation condition. Further, EMMAA only supported deterministic and continuoys ODE-based simulation of models.

We added support for a new simulation mode, namely continuous-time, discrete-space stochastic simulation using the Kappa framework. One important advantage of this approach is that - unlike the ODE-based approach - it does not rely on enumerating all molecular species that can exist in the system ahead of simulation. Instead, an initial mixture of molecular species is evolved, through a set of reaction rules, and new species can be created during simulation if any reaction rules produce them. However, stochastic simulation is typically slower than ODE-based simulation.

Further, we also implemented a new query mode for dynamical models that can be used to observe model behavior under perturbations. For instance, it allows answering the query “does EGF increase phosphorylated ERK?” in a model by setting up a pair of simulation experiments in which EGF is either at a low or a high level, and then quantifying the difference in the temporal profile of phosphorylated ERK between the two condition (the outcome is either “increase”, “decrease” or “no change”). This is useful for interactive user-driven queries but can also be used for model testing/validation against a specific set of observations.

There are numerous challenges involved in evaluating the dynamics of automatically assembled EMMAA models. For very large models such as the COVID-19 model, it makes sense to think of “executable subnetworks” that are assembled to answer a specific set of queries instead of attempting to simulate the entire model. We began implementing an assembly pipeline that performs additional filtering, reasoning and processing on assembled knowledge to prepare if for execution. These steps involve filtering to “direct” statements to remove indirect/bypass effects, rewriting molecular states in statements to improve the causal connectivity of the model, and filtering out “inconsequential” statements to cut down on the size of the model. We also implemented a new analysis feature that can detect potential polymerization (where molecular species can form arbitrarily large complexes as the system evolves) in a model which precludes ODE-based simulation and can result in slower stochastic simulation. For now, these detected polymerizations can help manually patch models, however, it might be possible to automate the addition of constraints to a model to avoid polymerization. Another problem is that of model parameterization. EMMAA models could be connected to relevant expression profiles to set total protein amounts as initial conditions, while reasonable priors can be chosen for reaction rate constants. Beyond that, the uncertainty in model parameters can be resolved by any combination of (1) fitting the model to data, (2) performing ensemble analysis that “integrates” over the model uncertainty, and (3) user interaction to set parameter values manually.

Creating a training corpus for identifying causal precedence in text¶

One of our goals during this period (in collaboration with the UA team) was to extend the Reach reading system with the ability to recognize causal precedence in text. An example of causal precedence expressed in text is the following sentence: “insulin binding of the insulin receptor (IR) at the cell surface activates IRS-1 intracellularly, which in turn activates PI3K”. This sentence not only implies that (a) IR activates IRS-1 and (b) IRS-1 activates PI3K but also speficically suggests that (a) is a causal precedent of (b). Given that not all A->B and B->C relationships that are independently collected necessarily imply A->B->C in any specific context, explicit descriptions of such knowledge are extremely valuable for understanding complex causal systems.

One challenge is collecting a large corpus of training data which consists of sentences with causal precedences descrbing some A->B->C causal chain without manual curation effort. Our idea was to start from curated databases to identify causal A->B->C sequences. Knowledge bases such as Reactome, KEGG and SIGNOR are organized into pathways, and the same molecular entity may appear in multiple pathways and be involved in different interaction in each pathway. This implies that to find relevant causal precedence examples, it makes sense to search for A->B and B->C relationships within the scope/context of a single curated pathway (instead of all curated knowledge combined). We ran this search on both Reactome and SIGNOR pathways and found that results from SIGNOR were higher quality and consistent with expected positive and negative controls.

Next, we searched all existing outputs from Reach to find instances of A->B and B->C relationships (from the set identified from SIGNOR) extracted from a single paper, and either a single sentence or two neighboring sentences. We found a total of 782 such sentences automatically. These sentences will become the training set for learning to recognize causal precedence.

We made our code available at https://github.com/indralab/causal_precedence_training and will continue to extend it to find further opportunities for automated training data collection.

Knowledge/model curation using BEL annotations¶

We have previously described an integration with hypothes.is. This integration has supported two usage modes: (1) users can select sentences on any website and add annotations in simple English language that can be processed into statements automatically, and (2) text mined statements can be exported and uploaded as annotations onto the websites (for instance PubMedCentral) where they were originally extracted from.

Though usage mode (1) is convenient, NLP on even simple sentences can sometimes be unreliable and therefore we decided to implement support other intuitive but formal syntaxes for annotation. Our preferred choice was the Biological Expression Language (BEL) which allows expressing a wide range of causal relationships relevant for biology. For instance, the BEL statement “kin(p(FPLX:MEK)) => kin(p(FPLX:ERK))” expresses that the kinase activity of the protein family MEK directly increases the kinase activity of the protein family ERK. Building on the PyBEL package and the existing BEL-INDRA integration we added support for parsing BEL statements from hypothes.is annotations into INDRA Statements. We plan to use this capability to build new human-curated models or extend existing ones in EMMAA.

Formalizing EMMAA model configuration¶

Each EMMAA model has to be set up with its own configuration settings in a JSON file. The settings allow to store model specific metadata (e.g. short and human readable name, links to NDEx visualization and Twitter accounts) that are displayed on the model dashboard as well as to configure the methods to update and assemble the model, run test and queries and generate statistics reports. With the number and diversity of EMMAA models growing we felt the need to document the requirements to the model configuration. The detailed instruction on what information the configuration file should contain with examples can be found at Configuring an EMMAA model